Quinoa and Amaranth: 500 years in oblivion

Upon their arrival, the “Conquistadores” found themselves faced with a world of new crops, some exalted (such as corn), others ignored, others still even banned, as is the case of Quinoa (and Amaranth). Quinoa was referred to as “the food of the Indians”. Furthermore, since we were in the era of the Catholic kings and Spanish Inquisition, its cultivation was forbidden to keep at bay the local populations that considered it a sacred plant. Probably, the European conquerors were not able to adapt to its taste due to the saponins, ignoring that, with washing, these substances would have been removed and the taste would have been much more pleasant. Since then, Quinoa was grown only for family use, in remote locations in the Andes, confined to hidden corners of the planet where native populations have preserved this seed and its cultivation techniques until today. Since the 1980s Quinoa began to arouse the interest of the US markets so that, from then on, the production began to increase in Bolivia and Peru and it began to be cultivated also in the United States, Canada, and in Europe (over the last 10 years).

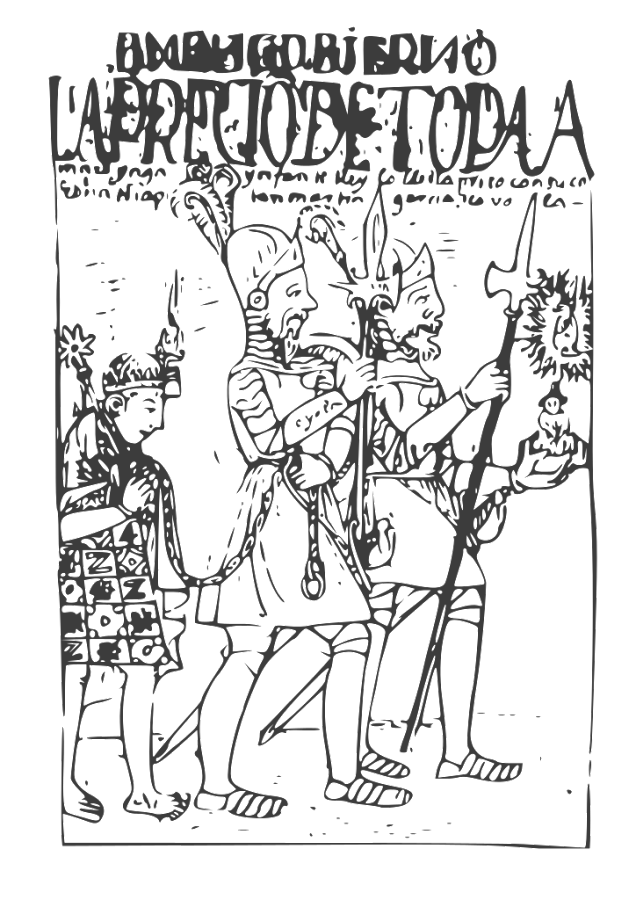

Amaranth, as well as Quinoa, has had a long and tortuous history, even being banned from cultivation after the arrival of the European conquerors in America. However, Amaranth, unlike Quinoa, was imported into Europe and there were cultivation trials, which, notwithstanding, did not bring to the desired results. Amaranth was thus used to decorate the gardens of European nobles, without food purposes. The big obstacle for Amaranth came from the religious and symbolic role that this plant played for the indigenous populations. Thanks to its quality as a plant that does not rot (hence the name of Amaranth, for its immortality) it represented the body of the Gods in religious rituals. Aztec women made a dough based on amaranth seeds, honey and blood (called tzoalli) with which they modelled the images of the bodies of the Gods, which were then eaten in a rite that was considered outrageous as it was considered a pagan version of Holy Communion. In addition to its sacred function, another factor that contributed to its almost total disappearance was the colour of its flower that the Christian conqueror associated with the devil.

For almost 500 years, the cultivation of Amaranth was also only carried out by small rural communities in remote corners of the planet but, starting from the 70s of the last century, it began to have success both in South America (especially in Mexico as an alternative to cereals) and internationally. Since the 1980s, its cultivation has gone beyond the borders of South and Central America, expanding into China, India and the United States. Presently, especially in Europe, its notoriety and consumption, although growing, are probably suffocated by the great success and media promotion that Quinoa is having, but in all likelihood, Amaranth will also soon be in the spotlight.